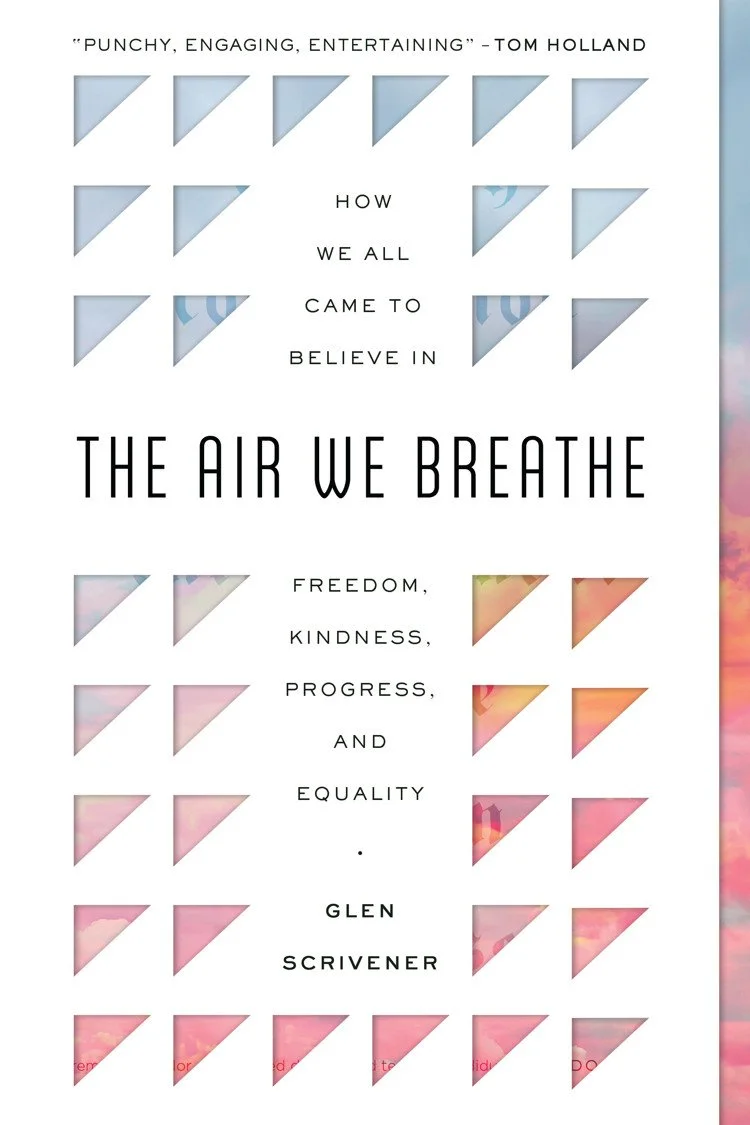

Book Review: “The Air We Breathe,” Glen Scrivener

Lately it has become fashionable to defend the Christian faith by showing how powerfully influential the faith has been over the course of western civilization. Tom Holland's book Dominion may be the most well-known book on this mission, even though Holland is not a believer, but Glen Scrivener's "The Air We Breathe" accomplishes the same general purpose, and in much viewer pages.

Scrivener shows that many of the values we take for granted in our modern progressive world actually are products of a Christian worldview. Compassion for the weak and vulnerable; equality among all people; the evils of slavery and sexual abuse; and the expectation of moral progress are all ideals not assumed in the ancient world. For instance, Plato said, “Justice consists of the superior ruling over and having more than the inferior.” Celsus said, “In no way is man better in God’s sight than ants and bees.” It is taken for granted today that these ideas are abhorrent, but most people don't know why. They take these assumptions by faith without knowing the foundation on which they stand.

The difference, according to Holland and Scrivener, is the influence of Christianity. Scrivener writes, "Western civilization is a vast, centuries long exercise in Jesus smuggling. At first it was overt; now it's covert . . . When we speak of humanity, history, freedom, progress, or enlightenment values, we are carrying on a Christian conversation." (p.207). Just as a fish doesn’t know it’s swimming in water, so most people don’t know they are swimming in a culture that is latent with assumptions gleaned from the Bible.

Scrivener quotes Jordan Peterson, who sums up a compelling dilemma: that he either believes that Jesus rose from the dead, which seems impossible; or he believes that a preposterous story “has stretched into every atom of culture,” which to him seems equally unbelievable. In other words, the fact that Christianity has penetrated every aspect of western civilization is a strong argument for its truthfulness.

My only slight criticism of the book would be that Scrivener sets the context for each chapter with reference to some contemporary event, often stemming from the social justice controversies that have erupted since 2020. This makes his arguments seem relevant, for sure, but as time goes on, the book could become rather dated to future readers.

But for now, this is an excellent way to get acquainted with the ample evidence for the truthfulness of Jesus’ parable of the leaven in Matthew 13 — “The kingdom of heaven is like leaven that a woman took and hid in three measures of flour, till it was all leavened.”